Campaigners often assume that people are more likely to be persuaded by someone who looks or sounds like them, someone of a similar age, gender, or background. After all, research has long shown that we tend to trust people who seem “like us.” But a new study challenges that assumption head-on.

In their paper, Shared Demographic Characteristics Do Not Reliably Facilitate Persuasion in Interpersonal Conversations (2024), Broockman, Kalla, Ottone, Santoro and Weiss put this idea to the test through a meta-analysis of eight experiments involving 6,139 participants across the United States. The studies examined persuasion in some of the most challenging issue areas – transphobia, abortion, immigration, and partisan animosity – through door-to-door canvassing and online video calls.

The question: Are people more likely to change their minds when the messenger shares their demographic traits?

The answer: Not really.

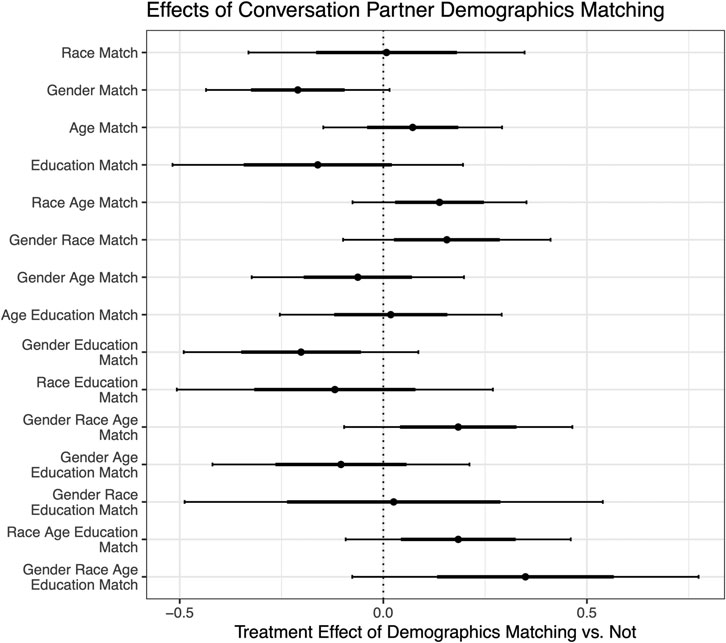

Despite common beliefs among both practitioners and scholars, the research found that shared demographics, such as race, gender, or age, do not meaningfully increase persuasion effects. The authors write that their results “rule out large differences” between canvasser-voter pairs with one demographic trait matching and pairs without it, suggesting that while tiny effects might exist, they’re unlikely to be strong enough to justify efforts to match canvassers to voters by demographic.

In other words, it’s not demographic similarity that makes a conversation persuasive, it’s the quality of the interaction itself. According to psychological “dual-process” theories, surface-level cues like a canvasser’s age or gender are only persuasive when people are not thinking deeply, unless relevant to the interaction. But interpersonal conversations typically invite careful thought, meaning substance matters more than similarity. It’s also worth noting that all the studies included in this research were conducted in the United States, so it’s not yet clear whether the same patterns would hold elsewhere.

However, there isn’t yet enough data to evaluate the effects of multiple overlapping demographic matches, for example, when canvassers and voters share both race and age, or gender and age, or all three. It’s possible that such combinations could have a layered effect, making similarity more noticeable and personally meaningful to the voter, and therefore slightly more persuasive. But in practice, these matches are rare and difficult to engineer in fieldwork. Until more evidence emerges, the best conclusion is that demographic matching has not been shown to produce large or reliable effects.

That’s encouraging news for campaigners. It suggests that meaningful conversations can bridge divides, and that effective persuasion doesn’t depend on finding a “perfect demographic match,” but rather on empathetic listening, shared values, and respectful dialogue. In the end, you don’t have to look like someone to connect with them – the power of persuasion lies not in who delivers the message, but in how it’s delivered.

Full paper: Broockman, D.E. et al. (2024) ‘Shared Demographic Characteristics Do Not Reliably Facilitate Persuasion in Interpersonal Conversations: Evidence from Eight Experiments’, British Journal of Political Science, 54(4), pp. 1477–1485. doi:10.1017/S0007123424000279. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-political-science/article/shared-demographic-characteristics-do-not-reliably-facilitate-persuasion-in-interpersonal-conversations-evidence-from-eight-experiments/6B7FA4A2CC36C4362C103BFDF97FB88C