At the final Campaign Lab Academic Series of 2025, we heard from Dr Katrina Lawall from the University of Reading. We often hear talk about helping support women entering office, but there is a problem that gets far less attention than recruitment: retention. Even where parties and civil society have made progress encouraging women to run, the “pipeline” of representation remains leaky, with women disproportionately more likely to drop out of elected office over time.

One major problem is that the costs of holding office are not evenly distributed. Women politicians face higher rates of harassment and hostility, both online and in person, and are more likely to carry caring responsibilities alongside the demands of the role. Formal institutional reforms, better reporting and enforcement around harassment, childcare provision, meeting accessibility and timing of meetings, and the practical burden of the job are essential. But they are often slow to implement, and many of the women currently in office are navigating today’s institutions as they are, not as we wish they were.

This is where Katrina’s research turns to peer support. Previous work suggests support from parties and informal networks can reduce the burdens women face, but access to those networks is uneven. The “old boys’ club” pathways that help men share knowledge, cope with informal norms, and find solidarity aren’t as available for women, particularly those who are newer to politics or further from the centre of local party structures. Peer support groups can provide a safer space for honesty and problem-solving, and can surface coping strategies and practical knowledge that are hard to ask for in hierarchical settings.

The study centred on local politics in England, with a particular focus on London. Local government can sound relatively community-oriented, but the lecture highlighted how it can still be intensely adversarial and sometimes especially hostile towards women in authority. London councils have higher levels of women’s representation than many parts of the country, but gaps remain, particularly in senior roles. Local politics also matters because it shapes substantial policy choices on housing, social care, and local services and it is a key springboard to higher office.

Using original survey data collected in 2024 from London councillors (with a notably strong response rate for an elite survey), the research team found clear gender gaps in the desire to stand again. Women were less likely than men to say they intended to run for re-election, and women also described council meetings as more hostile environments. Across the sample, many councillors reported low levels of support from their parties and peers, with a substantial share saying they did not feel supported by peers at all. Interviews reinforced this, with several women describing a sense that support was present during training and recruitment, but faded once they were actually in office.

To test whether support networks could shift these dynamics, Katrina and her co-authors partnered with Elect Her, a non-partisan organisation supporting women in politics, and ran a pre-registered field experiment. The full population of women councillors in London were randomly assigned to receive (or not receive) an invitation to join a real peer support network for women councillors. The invitation was delivered through multiple channels postcards and letters as a baseline, alongside outreach such as emails, phone calls, and messages where possible and outcomes were measured in a subsequent survey fielded by the researchers, designed to be unrelated to the invitation.

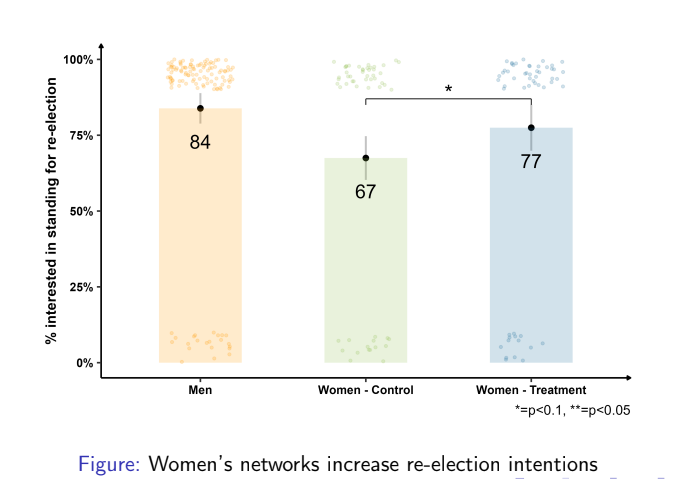

The results were striking. Simply being exposed to the invitation and the knowledge that this network existed increased stated intention to stand for re-election by around ten percentage points. In other words, a relatively light-touch intervention meaningfully reduced the gender gap in “static ambition” , the willingness to stay in the current role for another term. The team did not find a statistically significant effect on “progressive ambition,” such as intending to seek higher office, suggesting that peer support may be particularly effective at helping people endure and remain engaged where they are, rather than immediately pushing them to climb the ladder.

Qualitative evidence helped explain why this might be the case. Peer support offers horizontal solidarity rather than top-down advice, and can create a space where councillors feel able to speak openly about difficulties without worrying how it will be perceived inside their party. It can also enable early sharing of challenges before they escalate into crises that push people out of politics entirely. In the Q&A, Katrina also noted that where the outreach was most personal for example, where someone had a genuine phone conversation or back-and-forth exchange rather than only receiving written materials the effects appeared strongest, consistent with the idea that trust and felt connection matter.

Katrina argued that peer support is not a substitute for structural reform but that it might form one important piece of a wider package: formal reforms are necessary to reduce the unequal costs of office, but peer networks can help people cope in the meantime and can also act as a channel for information-sharing and collective advocacy. Knowing what reforms exist elsewhere, learning how to ask for them, and building confidence that these barriers are not simply “normal” can itself be politically enabling.

Towards the end, Katrina widened the lens beyond gender, drawing attention to underrepresentation that often goes unnoticed because it is rarely measured. One of the most notable findings from their broader survey was that renters appeared to be particularly underrepresented in local politics and more likely to consider stepping down, with potential implications for how housing and planning decisions are made. The dataset also pointed to disadvantages faced by councillors with caring responsibilities (including men), disabled councillors, and councillors from minority groups, where intersectional experiences can make local politics especially hostile and unsustainable.

The overall takeaway was a shift in how we think about inclusion. Getting underrepresented groups through the door matters but it is only the start. If we want representative institutions that last, we need to design for endurance: support that continues beyond recruitment, practical reforms that reduce unequal burdens, and better measurement of who is missing from politics and why. Peer support networks, the research suggests, are one concrete and scalable way to help prevent the pipeline from leaking once people finally make it into office.

——