Problem Addressed

Campaign Lab’s petition experiment aimed to identify effective communication strategies for mobilising non-electoral political action, specifically focusing on petition signing and peer recruitment. The study tested two core tactics: (1) tailoring email messages based on individual-level data to increase direct participation, and (2) mobilising supporters to recruit others within their social networks. The goal was to assess how personalisation and recruitment framing influence engagement within an already sympathetic audience and to explore ways to strengthen relational campaigning strategies.

Approach & Implementation

The research consisted of two randomised experiments conducted in partnership with an organisation’s mailing list audience in late 2024:

1.Personalisation Experiment – Over 11,500 individuals who had not yet signed the petition were randomly assigned to receive one of several types of emails. Variations included:

-

-

Generic, non-personalised messages.

-

Messages referencing the recipient’s self-identified top issue.

-

Explicitly personalised messages referencing the recipient’s top issue and stating that the message was tailored based on their prior input.

-

The primary outcome we measured was whether the recipient signed the petition.

2. Recruitment Experiment – More than 16,500 individuals who had already signed the petition were sent one of several types of emails:

-

-

A general update (control).

-

A general recruitment request.

-

A request to recruit a low number of additional signatories.

-

A request to recruit a high number of additional signatories.

-

Each participant’s unique sharing link allowed tracking of the number of new petition signers recruited through their actions.

Evidence & Evaluation

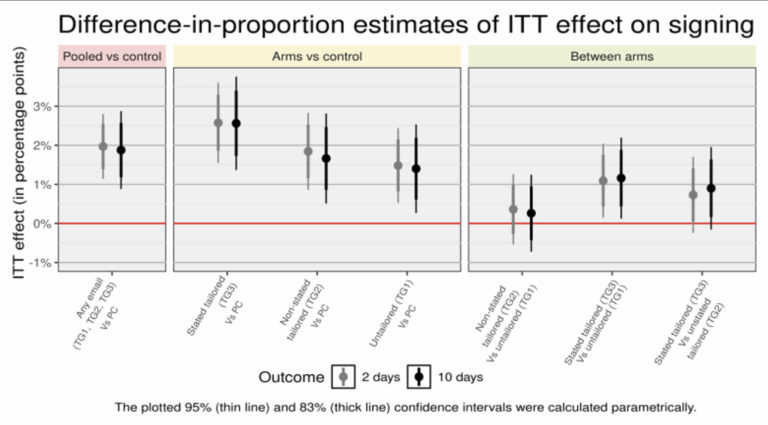

The personalisation experiment demonstrated that explicitly personalised emails were significantly more effective than generic or implicitly tailored messages. Sending any petition-related email increased signing rates by about 2 percentage points, while explicitly personalised emails achieved an additional 0.5-point improvement, for a total increase of 2.5 percentage points relative to the control group. This finding held across both immediate and longer-term follow-up periods. The results suggest that supporters respond positively when communications explicitly acknowledge their individual interests and past engagement, an indicator that the organisation is “listening.”

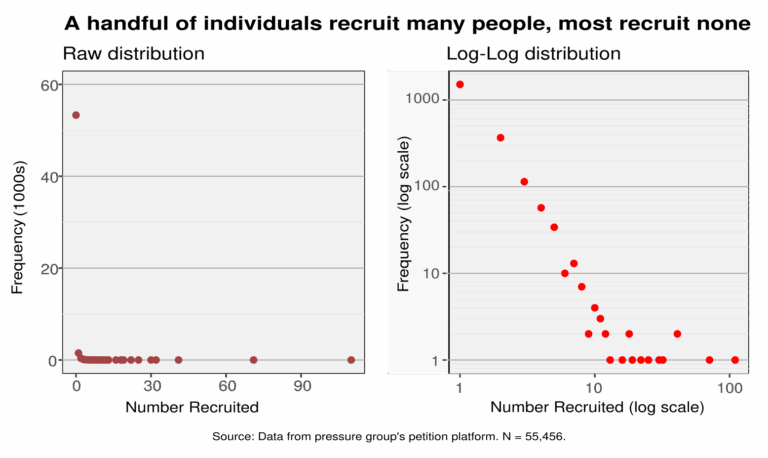

In contrast, the recruitment experiment yielded null effects. None of the recruitment messages, regardless of framing or numeric ask, significantly increased the number of new signers recruited compared to the control group. The data revealed a highly uneven distribution of recruitment activity: only 4% of participants accounted for all additional signatures generated, indicating a reliance on a small subset of “super-spreaders.” Most supporters did not recruit anyone.

Key Takeaways for Campaigners

-

Explicit personalisation works: Tailored messages that clearly state the basis for personalisation (e.g. referencing a supporter’s identified issue) can meaningfully increase participation.

-

Generic recruitment appeals do not: Simply asking supporters to recruit others has no measurable effect on mobilisation.

-

Future relational strategies must broaden participation: Because a small fraction of supporters drive most peer recruitment, campaigns should prioritise developing methods that engage a wider base rather than relying on a few highly active individuals.

Overall, this experiment highlights the promise of explicitly personalised digital communication for mobilising individual action, while revealing the limits of traditional peer recruitment tactics in achieving viral spread.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on our test. Your feedback is essential to improving our work, so if you have any comments or suggestions, please get in touch at [email protected]