In the tenth edition of the Campaign Lab Academic Series, Isolde Hegemann, a PhD researcher at the London School of Economics, presented early findings from a major new study examining how Republicans in the United States respond to different forms of fact-checking. Her work comes at a moment when the American information environment has shifted dramatically. In the days before Donald Trump’s second inauguration, Meta announced that it would abandon independent fact-checkers in favour of a Community Notes–style approach across its platforms. At the same time, the Trump administration has been using misinformation to justify policy goals and mobilise supporters, including highly conspiratorial claims shared directly on Truth Social. Republicans, who are disproportionately exposed to low-quality sources, have become a central target audience within this environment, making it crucial to understand how they react to the labels and signals designed to curb misinformation.

Isolde’s study set out to answer a deceptively simple question: when Republicans are shown pro-Trump political misinformation, which types of fact-checking – independent fact-checkers, community-based notes, or AI-generated checks – actually reduce their likelihood of engaging with it? She also wanted to know whether these interventions help people better distinguish between true and false information, rather than simply discouraging engagement altogether.

To answer this, she created a simulated social media environment that allowed her to observe participants’ natural behaviours, reposting, commenting, or choosing not to engage while still maintaining full control over what they saw. More than 1,450 Republicans were recruited and shown a mixture of real Trump statements, including twelve that were false and five that were verified as true. Some posts carried fact-checking labels, while others did not, and the source of the fact-check varied across independent fact-checkers, other users, and AI.

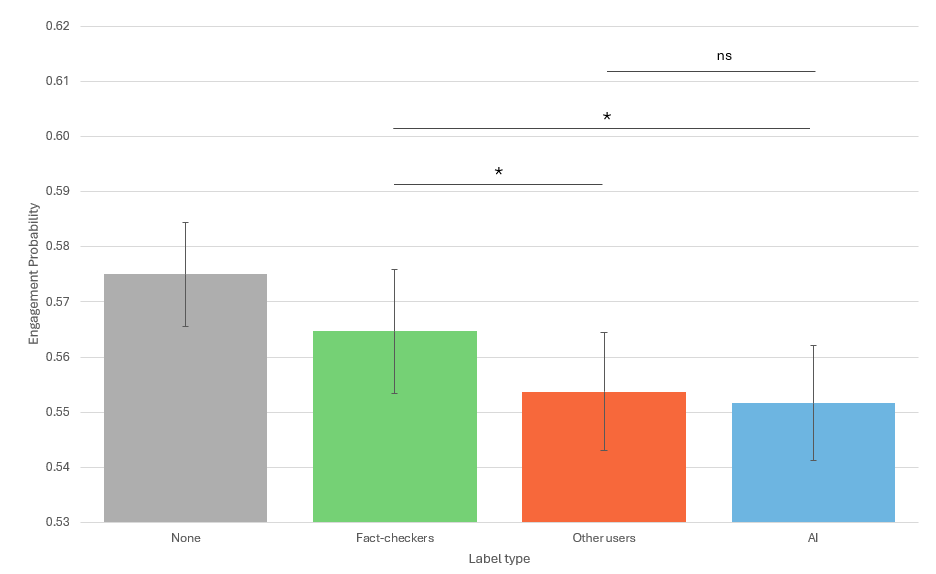

The results were striking. Fact-checking works. Even among Republicans looking at co-partisan misinformation claims that aligned with their political identity, fact-checking labels reduced engagement with false posts. The size of the effect was modest, but Isolde emphasised that even small behavioural shifts can meaningfully influence the spread of misinformation once multiplied through a social network.

The most surprising finding was the consistent performance of AI. Across the main model and all robustness checks, AI-generated fact-checking labels performed better than independent fact-checkers, and more consistently so than community notes. They produced the largest reduction in engagement with false information and remained effective even when the demographic composition of the sample was weighted to better reflect the Republican electorate. In contrast, independent fact-checkers had no statistically significant effect at all. This aligns with longstanding evidence showing that most Republicans distrust traditional fact-checking organisations and believe they are biased against conservatives. Community notes performed somewhat better, but their effectiveness was inconsistent and disappeared under more representative sample weighting.

Isolde also examined whether fact-checking helps users become more discerning. Here too, the news was positive. Fact-checking labels widened the gap between engagement with true and false statements, not by suppressing interest in the truth, but by discouraging interaction with demonstrably false posts. The labels did not drive people away from accurate information, suggesting that these interventions can help improve accuracy rather than simply reducing activity across the board.

The conversation that followed raised several questions relevant to practitioners. One area of discussion was whether such small percentage changes have real-world significance. Isolde noted that misinformation spreads cumulatively; if even a handful of users choose not to repost something, the reduced reach compounds rapidly. She also addressed concerns about the speed of traditional fact-checking, which is often too slow to keep pace with viral falsehoods. This, Isolde argued, is precisely where AI offers the greatest promise: the ability to process large volumes of content far faster than any human-led operation.

In addition we delved into the subject of whether AI might itself fall victim to false information or replicate biases baked into its training data. Isolde agreed that this is an important limitation. AI models remain black boxes, often trained on uneven or unreliable material, and prone to hallucinations. In her view, the most promising future lies in hybrid approaches where AI rapidly filters or triages potential misinformation, which is then reviewed by human fact-checkers who provide the final judgment. This preserves the scale advantages of AI while mitigating its vulnerabilities.

Another theme that emerged was why Republicans in particular seem so vulnerable to misinformation. Isolde pointed to the deep fragmentation of the US media ecosystem, where cable news and online echo chambers dominate, as well as the long-term effort by the Trump movement to undermine trust in neutral institutions. Many of the demographic factors present in the sample including lower levels of political and media literacy and the increasing sophistication of deepfakes also contribute to this vulnerability. Similar patterns, she suggested, are beginning to appear in Britain, particularly around fabricated immigration-related content and the spread of deepfakes during recent unrest.

Isolde closed by reflecting on the implications for campaigners and digital activists. Her research suggests that AI-assisted fact-checking may hold more promise for reaching distrustful or sceptical audiences than traditional institutional approaches. She also highlighted the value of simulated social media testing itself: activists and campaigners can use similar tools to prototype messages, test framing, or evaluate interventions before deploying them into the real world. As misinformation becomes more sophisticated and more central to political mobilisation, understanding what works and for whom will only grow in importance.

——