At the latest event in Campaign Lab’s academic series, we were joined by Dr. John Bryden, a researcher working at the intersection of politics, social science, and machine learning. With a background in software development and computational biology, Dr. Bryden led research at Indiana University’s Observatory on Social Media, where he studied how information and misinformation spread across online networks.

In this wide-ranging and thought-provoking talk, Dr. Bryden explored how online communities form, evolve, and ultimately shape political outcomes focusing especially on the rise of Donald Trump and the role of Twitter in the 2016 U.S. election.

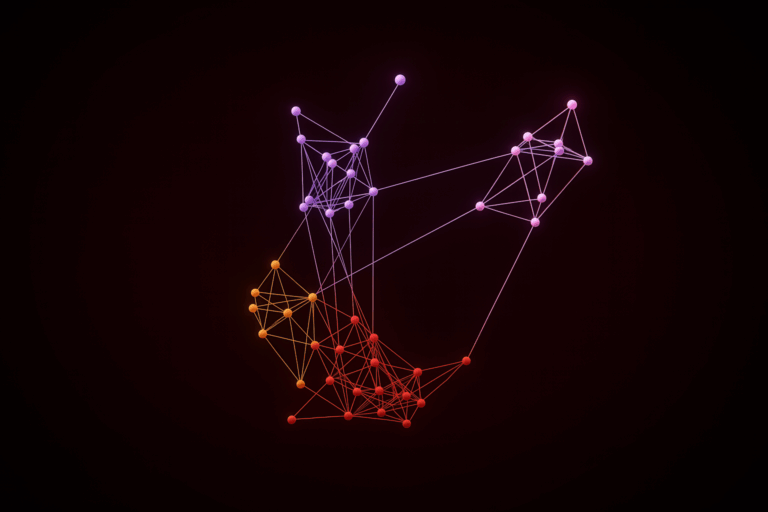

The session began with a crash course in network science. In Dr. Bryden’s words, online networks are built from nodes (usually people or accounts) and edges (the relationships or interactions between them). But these networks aren’t static – they evolve over time, and so do the communities within them.

Dr. Bryden first introduced some key concepts that help explain this evolution:

- Communities: Clusters of accounts that interact heavily within themselves, but less so with outsiders.

- Homophily: The tendency for people to connect with others who are similar to them politically, socially, or culturally.

- Social Transmission: The way opinions, language, and behaviours spread between individuals in a network.

He illustrated these ideas using simple simulations that showed how even a few basic rules could lead to the emergence of highly fragmented, self-reinforcing communities – just like those we often see on social media.

Using early Twitter data from 2011, Dr. Bryden and his colleagues showed that even in its early days, Twitter was not a giant, open forum – but a network of tightly-knit communities. From Bieber fans to healthcare policy wonks, people were already clustering in distinct online “tribes”.

Fast-forward to the 2016 U.S. election, and Dr. Bryden applied the same tools to study the online rise of Donald Trump. Starting from a single “alt-right” account, he built a network of 250,000 politically active Twitter users. This network revealed three key groups: Traditional Conservatives (GOP), Trump Supporters and the Alt-Right.

What stood out was that, over time, Trump supporters didn’t just emerge as a new group – they effectively replaced the traditional GOP network as the dominant force on the right. GOP users began to shift their attention and allegiance toward Trump accounts, while the alt-right remained a smaller, more fringe group.

Dr. Bryden described how Trump leveraged Twitter to speak directly to his followers, bypassing traditional media gatekeepers. As Trump’s follower count surged from 3 million in early 2015 to 13.5 million by election night, his tweets were amplified by an organically grown network of like-minded users.

This wasn’t, Dr. Bryden stressed, the work of bots. Using a detection tool called Botometer, his team found no significant evidence of coordinated bot activity in the Trump network. In fact, traditional Republican accounts showed slightly higher signs of automation possibly due to party-line messaging. Trump’s amplification came from real people: a self-organising, highly engaged social media community acting as a political megaphone.

The implications for campaigners are significant. As one attendee noted in the Q&A, it’s tempting to blame political shifts on bots or foreign interference but the data tells a more sobering story. The Trump Twitter movement was largely grassroots, if highly polarised. Building countervailing power on the left means creating equally engaged networks of real people who are willing to share, promote, and campaign for your message.

But that raises tough questions for progressive movements. As Dr. Bryden pointed out, the current social media landscape favours individual celebrity, centralised messaging, and sometimes narcissistic leadership styles traits that can be at odds with collaborative or collective values. How can we build distributed, ethical, progressive digital movements in a space that rewards the opposite?

The discussion ended with a look ahead. With the rise of platforms like Truth Social and BlueSky, and increasing disillusionment with X (formerly Twitter), Dr. Bryden acknowledged that the online political landscape may become more fragmented driven by both algorithmic inequality and ideological homophily.

Whether this fragmentation helps or hinders progressive campaigning remains to be seen. But one thing is clear: we need to understand how people organise, influence, and radicalise online – because that’s where modern politics increasingly lives.

——