The ninth entry of our Academic Series asked a deceptively simple question: how did Labour secure one of the largest post-war majorities in 2024 while winning a historically low share of the vote for a governing party? Professor Charles Pattie walked us through the mechanics of First Past the Post (FPTP) to explain why this election was such an outlier, and what it means for campaigners planning the next few years.

Pattie began by separating two ideas that often get blurred together. Disproportionality is FPTP doing what it usually does: converting votes into seats unevenly. By that yardstick, 2024 was extreme the most disproportional UK contest in recent memory. Electoral bias is different. It’s a structural tilt that means two parties with the same national vote can end up with very different numbers of seats. Using the classic Brooks method, Pattie ran a thought experiment: if Labour and the Conservatives had tied nationally in 2024, Labour would still have finished roughly 99 seats ahead. So the system didn’t just magnify the winner; it specifically advantaged Labour.

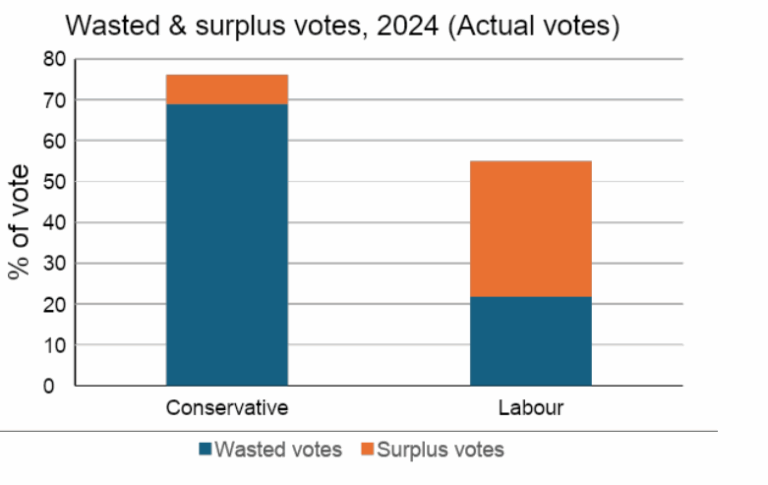

Where did that advantage come from? Three currents were doing the heavy lifting. First, efficiency: Labour “wasted” fewer votes fewer giant majorities and fewer near-misses so more of its ballots translated into MPs. Second, turnout: average turnout was lower in many Labour-held seats, which (counter-intuitively) reduces the number of votes needed per MP. Third, the pattern of third-party wins especially the Liberal Democrat revival hurt the Conservatives more than Labour. Meanwhile, two familiar sources of bias constituency size differences and the old Scotland/Wales effect have largely been neutralised by post-2011 boundary rules that tightly constrain electorate sizes.

If that sounds like a rerun of the late-1990s, Pattie’s warning was clear: this is not 1997. Labour’s position today is far more fragile. Many seats are held on modest majorities (a median closer to the high teens than the 30-point cushions of old), making the map quicker to flip on small swings. At the same time, voter volatility is at historic highs, with far more people switching parties between contests than a generation ago. Add the rapid rise of Reform UK, and you get a landscape where small national movements can produce very large seat changes and where a party can go from “wasteful” to “surgically efficient” overnight by nudging just past the winning line in lots of places.

The Q&A focused on what this means for practice. On Reform, Pattie hasn’t yet modelled the present polling world, but expects they could, at certain support levels, convert votes into seats with striking efficiency lots of narrow wins leaving them powerful yet vulnerable to any subsequent swing back. On turnout, he addressed a persistent myth: “higher turnout helps Labour” is only sometimes true. Mobilisation often stacks extra ballots in already-Labour seats, inflating majorities rather than creating new MPs. The implication is straightforward: targeting matters as much as raw GOTV energy.

Geographically, several long-standing patterns are melting. The big-city vs small-town divide still shows up, but not reliably and not everywhere. Traditional “nearest challenger” heuristics are less trustworthy when party standings are moving quickly and asymmetrically across regions. A recurring theme from attendees: years of neglect both in presumed unwinnables and presumed safes has left soft ground in multiple directions. Re-engagement takes time; waiting until panic mode is usually too late. And on message strategy, Pattie cautioned against trying to out-Reform Reform: if you campaign on your opponent’s strongest issue, voters may simply choose the original.

For organisers and practitioners, three takeaways stood out. First, build efficient geography: it’s not just about piling up votes; it’s about placing them where they create seats. Second, lean into core credibility rather than shadowing opponents’ frames; parties tend to win when they talk about what they are known for. Third, invest early in areas you’ve treated as either unwinnable or unloseable; both assumptions have a short shelf life in a volatile environment.

——