Last month, we had the pleasure of hosting Dr. James Ackland, a postdoc from the University of Glasgow’s Geospatial Data Science Group, who shared fascinating insights into how where we live influences how we vote. If you’ve ever wondered why polling can be spot-on in some areas but wildly off in others, this session offered some compelling answers.

We’re all familiar with the idea that demographics drive voting behavior; working-class voters lean left, middle-class voters lean right, and so on. This thinking underpins sophisticated tools like MRP (Multilevel Regression and Poststratification) polling, which has become increasingly popular over the past decade. These models can be impressive: they predict election outcomes by understanding demographic patterns and projecting them across constituencies.

However, demographics aren’t destiny. James showed us that while these models are generally accurate, they miss something crucial, context. The same person with identical demographic characteristics might vote completely differently depending on whether they live in Glasgow city center or a small town in the Scottish Borders.

So what exactly is a neighborhood effect? It’s the idea that the people around us influence our political choices beyond what our individual characteristics would predict. Think of it as political socialization in action. We’re not talking about your neighbor explicitly telling you how to vote while you’re mowing the lawn. Instead, it’s about how living in a particular community shapes the way you process political information and understand current events.

James explained four theoretical models of how this works, but the evidence strongly supports what’s called the “consensual effect”—people tend to vote more like their neighbors than demographic models would predict. You absorb the political atmosphere around you, and it genuinely matters.

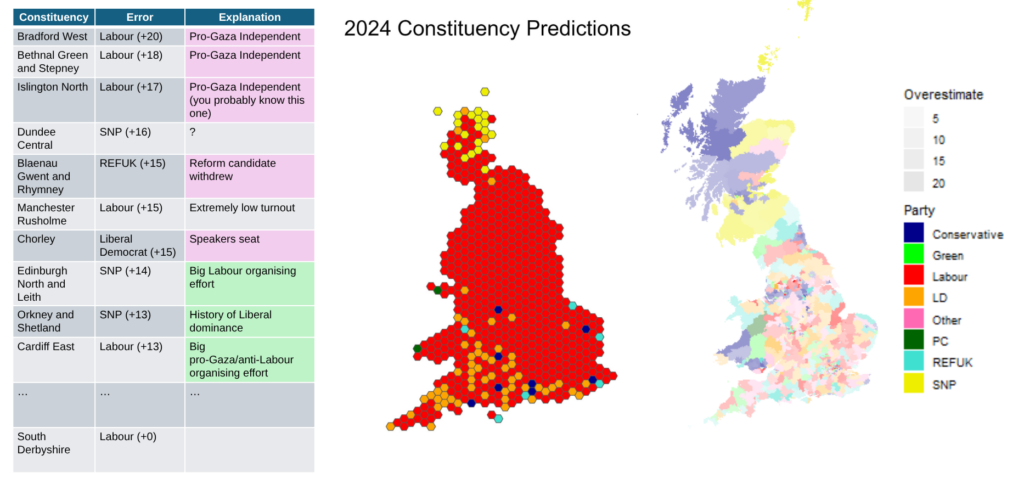

The real eye-opener came when James applied this thinking to the 2024 UK general election. By comparing his MRP model predictions to actual results, he identified constituencies with the largest “neighborhood effects”—places where something local overrode national demographic patterns.

The top three? Bradford West, Bethnal Green and Stepney, and Islington North—all featuring pro-Gaza independent candidates who dramatically outperformed expectations by mobilizing specific local communities. These weren’t random flukes; they represented coordinated organizing efforts that understood their neighborhoods better than any national model could.

Further down the list were constituencies like Edinburgh North and Leith, where strong local campaigns created swings away from what demographics alone would suggest. The message is clear: local organizing and understanding community context can create real, measurable change.

James was honest, he’s a data person, not a campaigner. But his research points to something crucial for all of us doing on-the-ground work. While some academics are skeptical about the effectiveness of campaigning (arguing that demographics determine everything, and political messaging is rarely persuasive), this research shows that’s not the whole story.

The takeaway? Spend time identifying constituencies where people might not vote as national models predict. Once you’ve found them, dig deep into understanding what makes them different. What are the local issues? What’s the community history? What conversations are people actually having?

When you’re up against well-funded opponents using big data analytics, your advantage is intimate knowledge of your patch. You know things the models don’t—because you live in the real world, not a spreadsheet. That local insight, combined with targeted organizing, can create the kind of neighborhood effects that swing seats.

As James put it, when you see a poll that gets your area wrong, that’s not proof the poll is bad—it’s proof you know something valuable the model doesn’t. Use that knowledge. Focus on hyper-local issues and community context, especially in an era where national campaigns might feel distant or overwhelming to voters.

The research confirms what many of us instinctively know: place matters, community matters, and organized local campaigning can move votes in ways that pure demographic analysis misses. Your street, your neighbors, your local issues—they all matter more than the data might suggest.

And that’s exactly where volunteer activists like us can make the biggest difference.